To Tackle Climate change, We Must Change Our Education Systems

“The generation educated today will have to do many things that the previous generation was not willing to do: prevent climate change, preserve biodiversity, stop deforestation, stabilize the world population, reduce the level of consumption […]” This was what David Orr, a professor of environmental studies at Oberlin College, wrote in 2001. The responsibility that today's generation must bear to overcome the threats posed by the environmental-climate crisis are unprecedented and, some might say, daunting.

One of the main questions we must continue to ask ourselves is whether our education systems are adequately preparing this new generation of children for an era of climate crisis, and in addition, whether they are providing these children with the knowledge and tools that will help them to overcome one of the biggest challenges of the twenty-first century? Unfortunately, more than twenty years after Professor Orr's words of insight and wisdom, there are many students around the world that graduate with very limited knowledge about climate change, and in some countries the topic is altogether absent from their schools’ curricula.

A thorough understanding of the climate crisis cannot be acquired by today’s generation by merely understanding what global warming is on a superficial level. Instead, each individual needs to be equipped with extensive and in-depth knowledge about the environment. Moreover, an ‘ecological compass’ should be bestowed on our children, which can renew a moral understanding of the relationship between humanity and nature.

In order to arrive at a pragmatic solution to climate change it is crucial to incorporate climate education in schools and other social settings. While setting concrete goals such as switching to renewable energy is an important step in the right direction, it does not guarantee meeting these goals. Only when the public will be exposed to the consequences that human beings’ activity have on the environment will there be more expectations, and perhaps pressure, on policy makers and politicians to ensure that such goals are met.

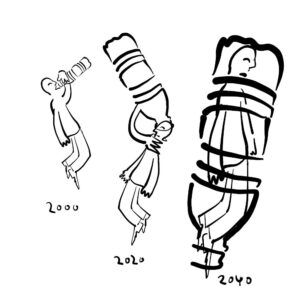

Apart from political steps, resolving the climate crisis involves many local initiatives and lifestyle changes. Streamlining waste at the level of local councils, lowering food consumption in every home, shifting investments from polluting companies by individuals, etc. The aggregation of infinite decisions together is what determines the level of carbon in the atmosphere. The solution requires a perceptual change and cannot be solely based on a bureaucratic agreement in summits meetings, at Glasgow, or anywhere else. The solution is to educate for an ecological compass, as well as pro-social and pro-environmental behavior. As long as we examine the proper use of nature with economic and utilitarian eyes only, disregarding moral justice considerations, we will not be able to solve the environmental hazards ahead.

Dr. Lia Ettinger, a lecturer at Tel Aviv University, invites us to imagine a world in which millions of young men and women join the labor market as they observe and interpret the world through glasses of sustainability: thousands of architects designing energy-efficient homes, engineers designing low-waste production lines and a million more young men and women in key positions. Even those who rely on technological solutions must admit that to inspire scientists to direct their creative and innovative skills towards solving environmental problems, sustainability education is needed.

Sadly, we still have a long way to go to achieve Ettinger’s dream. Most education systems are not preparing children adequately for the climate crisis. Also, education systems do not adequately train teachers and principals regarding this subject. As a result, many of them simply do not know how to teach it.

Among the many changes necessary, here are a few that should be prioritized: Firstly, training principals and teachers, and in particular teaching students, by asserting a basic compulsory climate education course for them. Secondly, defining climate education as a core compulsory profession for all ages. Thirdly, establishing a professional committee that integrates the issue of climate education on the ministry level. Fourthly, budgeting the installation of structural preparations for the school's emergencies (floods, fires, storms, etc.). Lastly, some additional changes include installing solar panels, mapping sources of greenhouse gas emissions, and develop a plan for energy efficiency accordingly.

Optimism can be derived from the progress that has already been made. In 1992, 12-year-old Severn Cullis-Suzuki gave a speech at the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit in which she criticized the older generation and world leaders for environmental crimes and rising poverty. Suzuki's reviews had received a wave of public outcry, but that wave receded just as quickly as it had started. The public was not ready nor willing to accommodate the scale of Suzuki's demands. Educational work and knowledge are required to understand the significant changes that we as a society must undergo. Thirty years after Suzuki's speech, a comparison can be made between the public's response to her and the public’s response to Greta Thunberg. The world is now arguably more prepared for the change needed. Thunberg has been invited to speak at dozens of international conferences and has won extensive media coverage. It seems that the source of influence, more than it lies in the leader, lies in our maturity as a society to listen and understand. We can imagine the extent of the social response to the next leader if climate education will be a fundamental profession in schools.